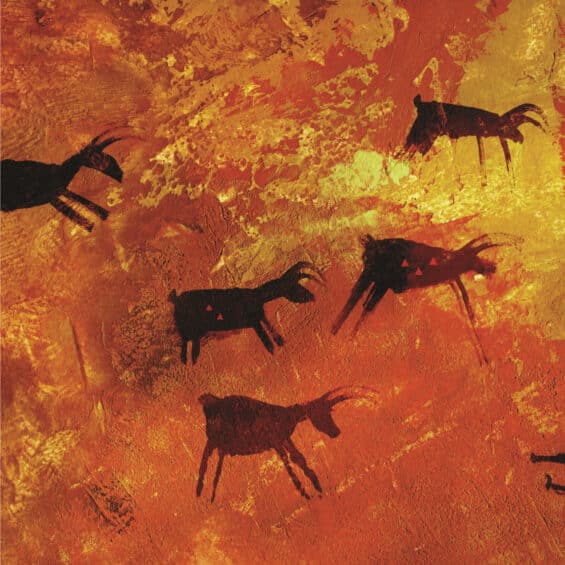

The last upgrade that the human brain went through in our evolution as a species was the development of the pre-frontal cortex, approximately 70,000 years ago.

Homo Sapiens began marching to a very different beat of evolution, and human cultures began to take shape through the medium of language and the ability to communicate in increasingly sophisticated ways.

Free to think of “what could be”, humankind rose to the top of the food chain and began transforming the environment to make it more amenable for survival.

Purpose

Imagination, or as cognitive scientists term it, “represented reality”, brought with it the complex need for purpose, something that was hitherto unnecessary. The need for purpose has arguably been one of the most powerful vectors of evolution. Not just satisfied with what is, but needing to know the reason why, has been the source of extraordinary development in almost every aspect of existence, from philosophy, science, technology and medicine to literature, art and poetry in every civilisation in the world.

Purpose became an important tool for human beings to devise more sophisticated ways to thrive in the hostile climate of sub-Saharan Africa. Seeking out purpose emerged as a fitness-enhancing adaptation as it allowed for group cohesiveness. In that sense, this is hardwired into our consciousness as an evolutionary mechanism.

Empathy

The complexities of developing relationships led to the development of another vector, that of empathy. Along with the need for purpose, this marked a major evolutionary breakthrough in the development of the human brain.

As neuroscientists put it, the computational requirements of dealing with a hostile environment and the need to interact and communicate with others, sculpted the empathetic function.

Empathising with the other is a highly complex evolutionary ability, requiring a sophisticated coordination between our sensory systems (detecting feelings), and emotional systems (mirroring emotions). When infants cry at the recorded sounds of other infants, or when our tear ducts involuntarily produce tears at the sight of another’s suffering, it demonstrates how an ancient adaptive ability to empathise continues to throb inside the brain.

Meaning

The two vectors of purpose and empathy were responsible for the creation of meaning as a crucial turning point in our development as a species.

The quest for meaning would go one to become the most important requirement for the human brain. A lot of people tend to view purpose and meaning as interchangeable words, but in reality, they mean entirely different things.

Meaning is the result of putting our purpose to work into a larger context, something that is much larger than us. We tend to think of meaning as something to be found and to be held on to; on the contrary, it is exactly the opposite.

Meaning appears when we find ourselves making a positive difference; when our lives and work become meaningful to the other. That is precisely why, meaning only occurs in the act of relationship, it is not a solitary activity. Interestingly, it only manifests itself in the act of giving rather than taking! And consequently, we feel a loss of meaning when we find ourselves not contributing or being of service.

If meaning is so important to us as a species, why do we not protect it as a resource?

Interestingly, the same upgrade in our brains that evolved the need for meaning, also evolved what neuroscientist and philosopher Francisco Varela termed “know-how”: the conditioned autopilot through which we navigate our way through life. Quite unconsciously we are conditioned in our societies to subscribe to the dominant narratives of our age and culture.

So, concepts such as survival of the fittest become the cultural template that conditions us to believe in the fang and claw model in which everyone is out to look after themselves. In fact, if you were to examine the dominant mythologies that have shaped our understanding of ourselves and our thinking and behaviour over the past few hundred years, these mythologies have put individual interests before anything else.

Dehumanising our natural environment

In the process, we have become dehumanised to our natural environment, and to the larger communities in which we exist. We feel rather strongly, that this narrative has reached the end of its usefulness, for two key reasons.

- The very environment that keeps us alive has overshot the limits of sustainability. Global warming is but one example. The devastation of our natural ecosystems through toxic wastes like plastics, and the inability of our environment to support the growing population of the planet, is ripping through not just the very flawed logic of seeing ourselves as separate from nature, it is nothing short of critical for our very survival.

- We now live in a complex and interconnected world, fueled by digital technology and global information flows. Wired up like a gigantic network, the 21st century is rendering old mythologies of nation-states, and the ‘us’ versus ‘them’ mindset that were manifestations of a more tribal world utterly obsolete. Complex problems such as global warming and pandemics simply cannot be solved unless we learn to collaborate and approach the problems from a systems perspective.

The gap between a 21st-century hyper-networked world of interconnections and inter-dependencies with an unprecedented ability for mass collaboration, and our pre-industrial age mindset has become alarmingly large.

It is time for us to completely transform the very foundations of our worldview.

We must build and manage our organisations and societies from a genuinely new 21st-century perspective that honours our long lineage. The two vectors of purpose and empathy, that we carry embedded in our pre-frontal cortex are our resources for leadership in the 21st century.

Rehumanising leadership is about transforming our organisations to operate from the axes of purpose and empathy with a view to creating meaningful impact on the external environment of nature, market and society, and the internal workplace of the people that work with us. And that in a disruptive and fast-moving 21st century where digital technology, global information flows and a new millennial demographic are rewriting the very rules of work, life and leadership.